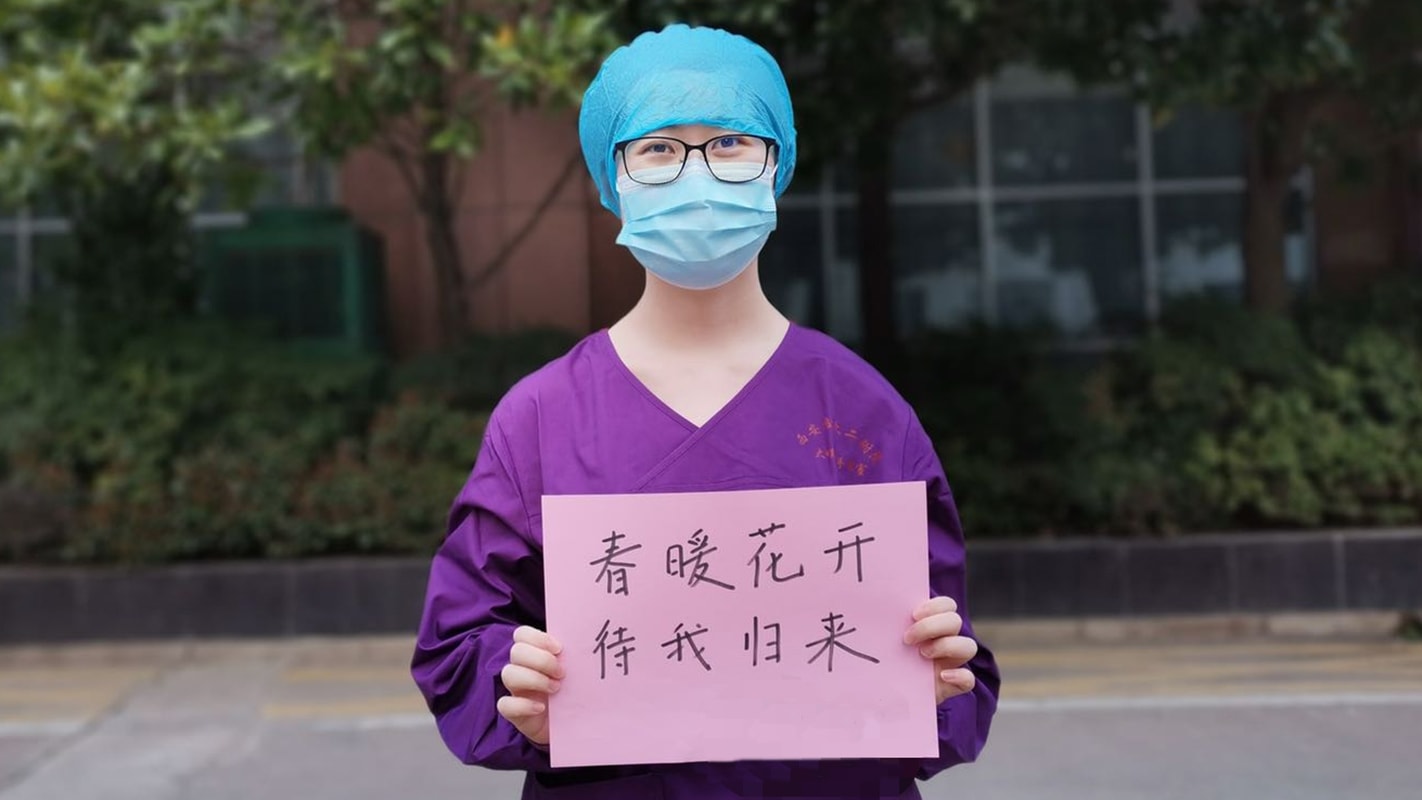

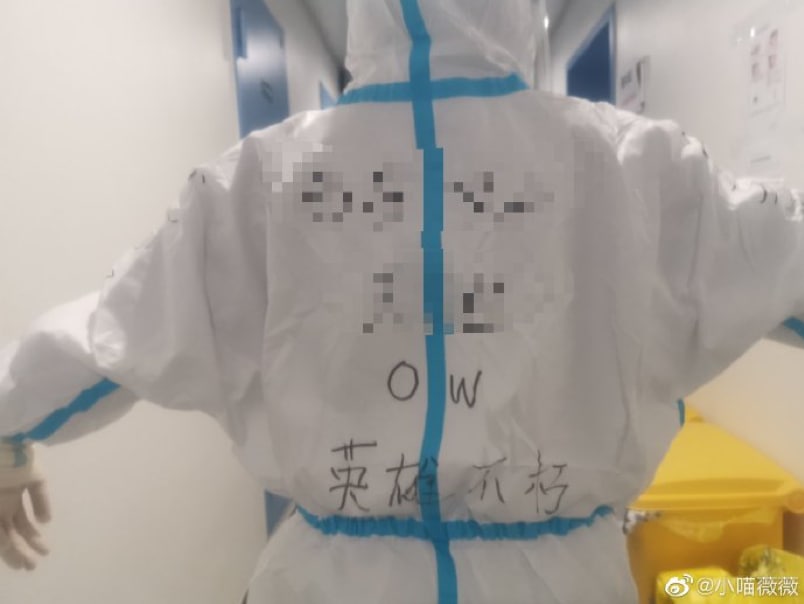

Countless times, she had put on a hazmat suit and goggles and passed through the four doors of the makeshift sterilized area into the infirmary that had been converted from a normal hospital space into a COVID-19 ward. Because she’s small in stature, the bulky suit impeded her hurried steps. On her chest, her name was written in black marker, and on her back was the phrase, “Heroes Never Die.”

Her name is Weiwei. She is a regular Overwatch player, as well as a member of the National Medical Team from the Xi’an Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiantong University in Shaanxi Province, who was dispatched to assist in the Hubei province during the COVID-19 outbreak.

At age 27, Weiwei was the youngest doctor in the Shaanxi Province team. She volunteered after receiving a request from the hospital on Feb. 7. The team left Xi’an on the evening of Feb. 8 for Hubei and arrived at the vicinity of Tongji Hospital in Wuhan the same night.

Her maternal grandfather was a veteran of the Second Sino-Japanese War who enrolled at the Counter-Japanese Military and Political University. Her father attended the military academy in Wuhan and served as an officer. When it was Weiwei’s turn, she also put military academy as her first choice after high school. Unfortunately, a congenital eye defect derailed her dream of military service. Undeterred, she applied successfully for both undergraduate and master programs in clinical medicine at Jilin University—programs with the highest admission score for enrollment at the school.

After graduating from Jilin University in 2019, Weiwei returned to work in her father’s hometown, Shaanxi, as a cardiologist for the Xi’an Second Affiliated Hospital. Although it was just her first year as a professional, she was determined to fight an unpredictable and dangerous battle. Before leaving for Wuhan, to make it easier for her to don the hazmat suit, she spent 15 minutes cutting off the long hair that she had grown out for years.

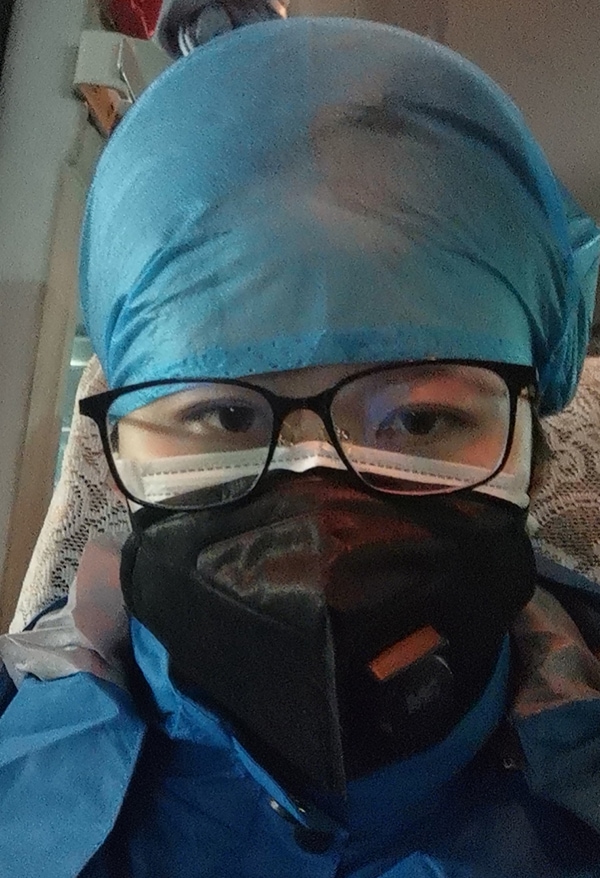

In a selfie that she posted to Weibo, Weiwei is wearing double layers of masks in her seat on the airplane. “It was not necessary to wear two masks, but I was so scared and that was the only way to calm myself,” she recalled.

On the 90-minute flight from Xi’an to Wuhan, Weiwei kept mentally preparing for the worst—the possibility of dying in service. One of her female colleagues, she said, secretly wrote a will.

In the “Honor and Glory” animated short for Overwatch, Balderich of the Crusaders sacrificed himself at Eichenwalde Castle to protect Reinhardt and fellow soldiers, passing the Overwatch torch to Reinhardt in the process.

“Soldiers go to war. Police catch criminals. Firefighters fight fires. I’m a doctor and it’s my duty. I should not run away from it,” Weiwei said. “I have been called, so I must answer. Always.”

The work environment in Wuhan was actually much better than Weiwei imagined. Shifts were busy and lasted two to three days, and afterward she still had to take a decontamination shower back at the base. It left her completely exhausted, but then she got two to three days off afterward to fully recharge as well. Weiwei and her team stayed in a hotel during their time in Wuhan, each with their own room to maintain distance; dedicated staff would prepare food and drinks, including fruit. Some days, she was even served yak jerky and caterpillar fungus donated by the people of Qinghai, her hometown.

Still, the food and lodging couldn’t even begin to compensate for the threat to their lives every day. The perils of their job far outweighed what they got back in return; no perks could measure up to their courage and spirit.

Tongji Hospital in Wuhan primarily accepted and treated the critically ill, making Weiwei’s job even more formidable. It took her more than an hour to strip out of her hazmat suit every time, and she had to wash her hands for one minute after every single step. “It was very stuffy in the suit,” she said. “All I could think about was getting out of it, but common sense told me to be patient.” Every hazmat suit was single-use only, so everyone tried to conserve however they could. To cut down on the number of changes, they wore adult diapers underneath when they went into the contaminated area.

Doctors like Weiwei had to check on patients every morning. And if a patient experienced complications or needed urgent care, the doctors had to go back in again. For the medics, every trip inside carried high risk, and they fought their fears while looking death in the eye.

On Feb. 16, Weiwei posted on Weibo about treating a COVID-19 patient for the first time.

“I think I was destined to be a doctor,” she wrote. “On the day shift yesterday, I was sent to perform a throat swab for a COVID-19 test. It was a highly risky procedure. A patient could cough or even vomit in the presence of exposed medical personnel, but the ER doctor still took me along. Frankly, I was scared to face a COVID-19 patient for the first time. I could feel myself laboring to breathe under the protective mask. But once I was next to the patient, it was like I had gotten back to the familiar CCU and the fear vanished. He was just a patient, me a doctor. After finishing the examination, I recalled that before I left home, my mother had asked me why I wanted to go, and I replied to her that I was a doctor.”

In the middle of hardship, the doctors and nurses took joy in turning their white suits into canvases for hope. Weiwei said the medical team found their creative spirit: some drew iconic buildings in Wuhan and Xi’an on their suits to show camaraderie between the two cities, others drew their favorite singers on their back, and still others wrote well-wishes to their kids across their chest. Weiwei thought about writing the name of her cat—a playful, affectionate American shorthair—but let that idea go since cats can’t read. Then she considered writing her parents’ names, but she was afraid that her mother would cry seeing it.

Activision Blizzard Commits to #PlayApartTogether

Share your gaming setup and favorite moments with us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook using the #PlayApartTogether hashtag.

Finally, she settled on “Heroes Never Die.” The head nurse even added a pair of wings with a marker.

On May 23, 2016, one day before the Overwatch server launch, Hongyu Wu, a 20-year-old student at the Industrial College of Guangzhou, made his last post on WeChat before dying in his pursuit of a suspected motorcycle thief: “Anyone looking forward to the Overwatch launch tomorrow?” His name was inscribed in the game’s Lijiang Tower with three words—“Heroes Never Die”—on the wall.

Like every Overwatch player, Weiwei is familiar with Wu’s name and story. She calls him a real hero. “He could have let it go and no one would have blamed him in such danger. Yet, he still did it without hesitation. He is a hero. But not me, I’m just doing my duty as a doctor.”

From arriving at Wuhan on Feb. 8 until mid-March, Weiwei treated more than 100 patients at Tongji Hospital, two of whom left particularly deep impressions. One was a 21-year-old who couldn’t wait to be discharged and volunteer after recovering. The other was an elderly man whose son and daughter-in-law were both doctors. He was infected by the son who had caught it working in a hospital.

Weiwei asked him if he ever regretted sending his son to med school. The old man replied, “Never.”

When the man was discharged, she took a selfie with him in the lobby. Before he left, the elderly gentleman told her he would go donate blood after quarantine.

On her days off in the hotel, Weiwei would still stay in touch with patients through WeChat. A sort of competition also developed between colleagues, who would “brag” about the recovery progress of their respective patients. “When I talked to colleagues about how one of my patients was able to shower that day, I’d get a sense of superiority,” Weiwei joked. But one day, when an elderly patient told her he could finally bathe and do laundry all on his own, it almost moved her to tears.

On the night of Feb. 8, when she first arrived, Weiwei posted a message to the Overwatch hot topic tag on Weibo: “The world could always use more heroes. I’m finally off to the frontline to destroy the virus after my 600+ hours on Angela.” Over the next few days, the message was reposted 500 times, with almost 500 comments and 3,000 likes. Fellow Overwatch players encouraged Weiwei in their replies, urging her to emerge victorious. Some even joked about not eliminating the enemy Mercy in their games for two months.

Even now, Weiwei sees more and more likes and support for that post. In Wuhan, she made a habit of logging in almost daily to read the comments and private messages. “It pumped me up every time,” she said.

As a doctor, Weiwei spent most of her time in the cardiology ward over the past year, often providing emergency treatment to critical patients and remaining on 24-hour standby even off-shift. Overwatch and the Overwatch League occupied almost all of her spare time. Whenever Weiwei felt depressed in Wuhan, she’d check out Overwatch videos or Overwatch League matches. As a fan of the Chengdu Hunters, especially Hu “Jinmu” Yi and Menghan “Ameng” Ding, she would be elated for an entire day when they won, and couldn’t bear to rewatch a match when they lost.

“To be honest, there’s an ulterior motive to my Overwatch post on Weibo—I wanted more people to know gaming is not a taboo,” she explained earnestly. “We each have our own beliefs and responsibilities. Games are not scapegoats. They let us face life in a positive light, and you can count on friends you made through gaming.”

Influenced by her father, Weiwei started playing games when she was very little, finally finding a home in Overwatch. Beyond just an interest or hobby, the game inspired her beyond pure entertainment—it helped her fulfill her old dream of being a soldier and fighting alongside teammates. After nearly 1,000 hours as Mercy, Weiwei has developed a habit of reviving teammates in dire situations; she says it gives her a sense of accomplishment and reward.

“I’d doubt myself whenever I couldn’t save any patient from complications, going over what I might have done wrong in my mind,” she said. “So I wasn’t about to give up on any ally in the game. I’d do whatever I can, even taking a bullet.”

On March 21, the day before she left Wuhan, Weiwei posted a shot of the city streets at 7 a.m., as the rising sun cast a soft glow between buildings. She captioned it: “Everything has awakened.” As Wuhan took a turn for the better due to the collective efforts of medical personnel from throughout the country, so did her mood.

It was her first time in the city, but she had never had a chance to take a good look at it. Once, their transit bus purposely made a detour through the city, allowing her to catch a fuzzy, distant glimpse of Yellow Crane Tower through the window. The bus went by the Wuhan Bridge and she waved at the police patrol. They returned the gesture by saluting the vehicle.

The world could always use more heroes. This sentence has been echoing through Weiwei’s mind from the moment she filled out the volunteer form, throughout her journey and her time working in the ward.

Sometimes it doesn’t take a sacrifice to make a hero. Weiwei became a hero the moment she made that difficult choice. Time passes, but heroes never die.