EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is a part of a series of deep dives on topics in Gameplay Systems, specifically the Competitive/Social & Player Dynamics space of VALORANT. Learn more about the series in our intro.

Hi everyone, we’re Brian Chang and Sara Dadafshar, members of the Social and Player Dynamics team on VALORANT. In this article, we go in-depth on our past and ongoing work to detect and mitigate AFK (Away From Keyboard) behavior.

INTRODUCTION - THE WAY INTO THE AFK PROBLEM

Someone who is “AFK” is someone who leaves or otherwise does not participate during an ongoing game. Most multiplayer games have an issue with AFKs, and all competitive team-based multiplayer games face this issue to some degree or another.

VALORANT is no exception but that doesn’t mean we can’t discourage disruptive behavior. An AFK in a game compromises the competitive integrity of the match (matches aren’t fair if it’s a 4v5), and as a result downgrades general enjoyment of the game. It’s something we knew was a must-solve for players early in the development of the Social and Player Dynamics team.

Earlier this year we updated you on the work to inhibit AFKs (along with some other stuff), where we talked about some improvements that we’d already made and other work that was in progress for AFKs.

When addressing AFKs, we wanted to make sure of a few things:

- We don’t punish you for unlucky games. Stuff happens (your cat “accidentally” kicks the power cord out) and we don’t want to punish you for rare, unfortunate circumstances that are out of your control.

- We want a scalable way to detect AFKs that avoids false positives. It would be really bad if someone was holding an angle for a while staying completely still and we flagged them as AFK.

- We want to make sure that there are clear signals that we can measure to see if our efforts are successful. Without these benchmarks, it would be hard for us to know whether our work actually made a difference, or if you’re still encountering the same amount of AFKs.

WHAT HAVE WE DONE SO FAR?

March this year was our first foray into a system to find AFKs. The simplest version of this system (which is what we started with) was to look for people who had either disconnected from the game, or stayed completely inactive for a prolonged period of time.

This covers most AFKs (from internet going down, to rage-quitting, to cats), but it left us room to improve. Specifically, we didn’t yet cover the potentially more malicious AFKs: people who intentionally do not participate in the game, but stay “active” in the game so as to not get disconnected. These are often the worst to deal with—they intentionally look to ruin the experience of everyone, especially teammates.

To address these situations, we set trackers to look for specific behaviors and metrics in-game that we can then tie to AFKs. We can’t get into specific detail about those trackers (since revealing how we detect AFKs would make it easier for bad actors to bypass those rules). What we can say, however, is that our focus was to make the detection process heavily scalable. When a new behavior or method of detection is identified, it is very easy to look for it in our system (and take action when we find certain behaviors).

Finally, we wanted to make sure punishments for AFK were fair (forgiving for people who AFK on a rare occasion, but severe for serial leavers). To accomplish this, we created an AFK “rating” per player that tracks their AFK behavior across all of their games played. The more a player commits AFKs, the lower their rating becomes, and the harsher their punishment will be on a future violation.

In other words, if you’re a player who rarely or never goes AFK, then your AFK rating will be good, which means that if you do happen to accidentally AFK in a game, you won’t be punished severely (for example, you’d receive a warning message).

Conversely, if a player rage quits every other game, they’ll quickly find themselves going from receiving a warning, to XP denials, to queue restrictions, and eventually banned from playing the game as their rating tanks. Throughout the process of escalating penalties, they’ll have multiple explanations of why we took action, and what behavior they need to change...in case they come crying.

We also wanted to make sure we avoided edge cases, like leaving in the middle of a Deathmatch game. If a player AFKs in Deathmatch, the harshest punishment they will receive is denial of XP for the game that they were AFK in. This is because being AFK in a Deathmatch doesn’t ruin the experience of teammates (everyone is your enemy in Deathmatch). However, we did notice a sizable number of accounts who were farming XP in Deathmatch by entering a game and going AFK.

THE RESULT?

None of this talk matters unless it actually improves your experience playing VALORANT. So how do we find out what worked?

There’s a couple of data points that we look to measure this. We could spend a whole article talking about just the data (in terms of how we measure, potential biases, etc.), but here are some of our benchmarks:

- AFKs Detected Over Time

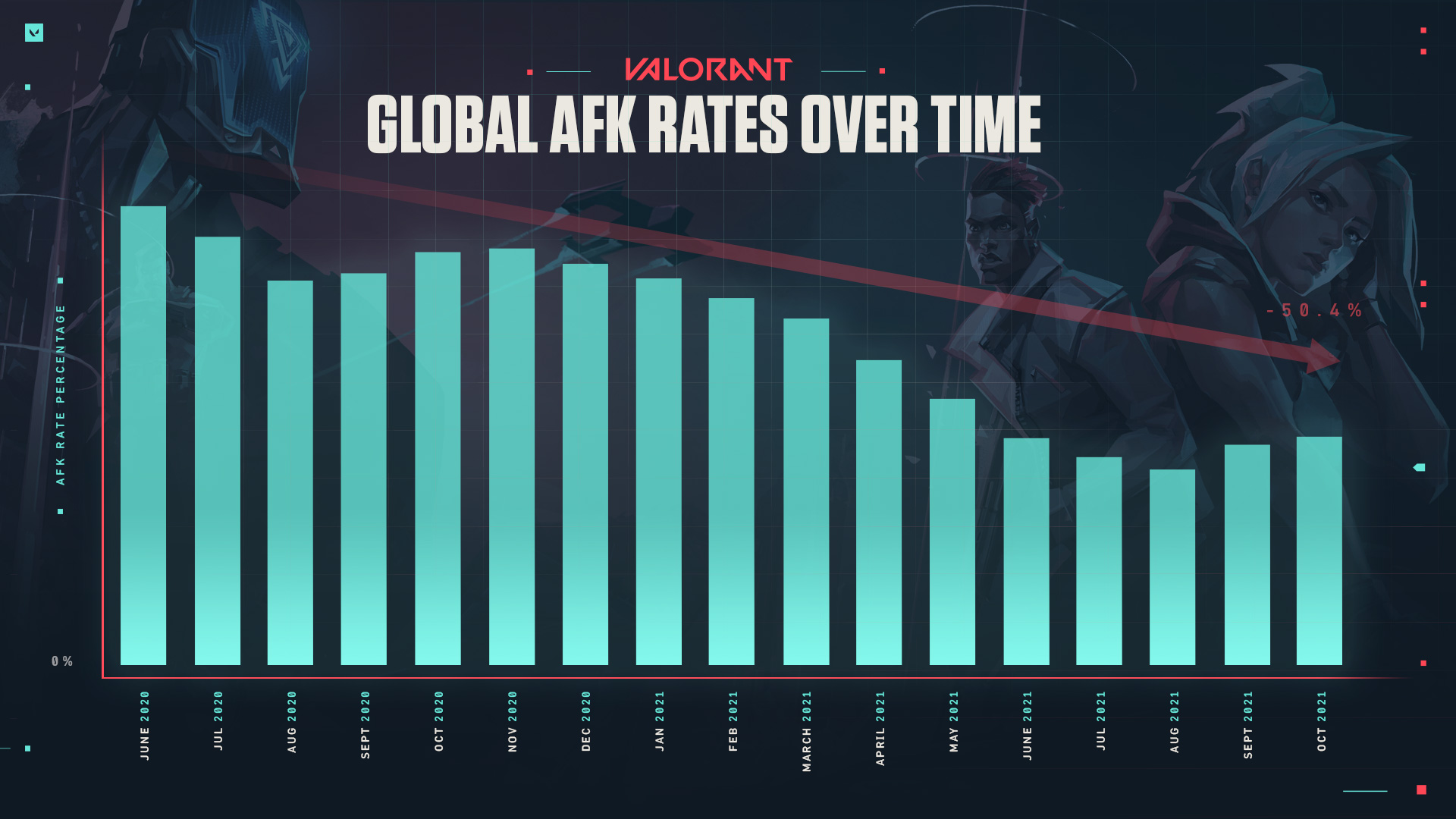

To start, here’s our detected severe AFK rate (number of AFKs per game) over time in Unrated and Competitive games. For this graph, we define “severe” AFKs as anyone who is detected as AFK for 6 or more rounds in a match.

The AFK rate stays at a similar level for the first six or so months of launch, but we see detected AFKs take a dive in early 2021. This lines up with when we started implementing our improved AFK detection and penalties.

Overall, the AFK rate in games has more than halved over the last year! Things have once again stabilized at a new, lower value.

- AFK Reports

One problem with measuring detected violations is that we don’t really know about AFKs that our system isn’t detecting. Overall, we’re confident that AFKs have gone down, but it’s unclear how much more work there is to be done. One way that we can measure whether you truly feel like you’re experiencing fewer AFKs is to look at report counts.

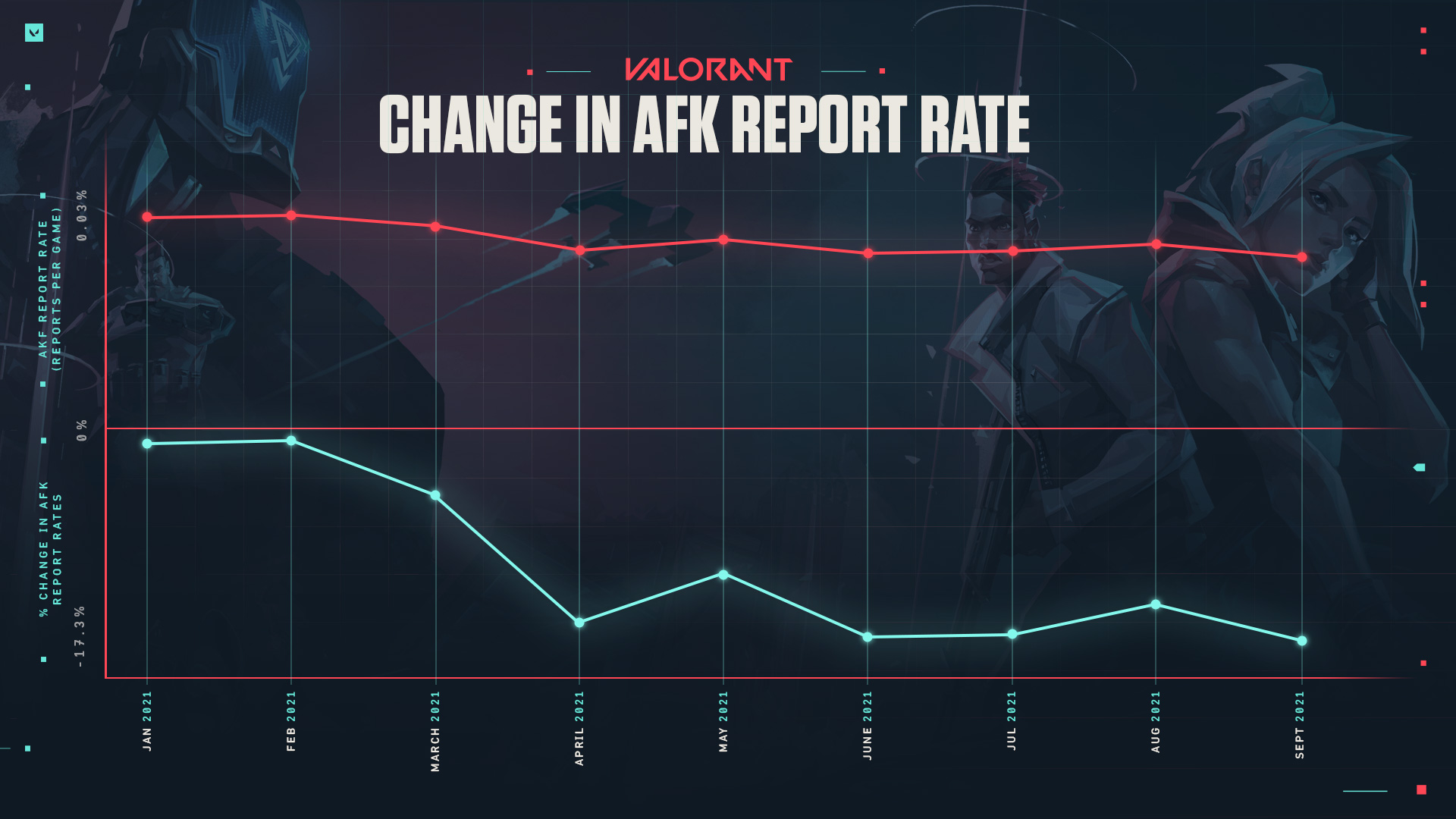

The top graph shows AFK “Report Rate,” the number of reports we receive for AFKs, normalized for hours played. The bottom graph shows the percent change in the AFK report rate over time since the start of the year. As you can see, after a drop in March, report rates are down around 17% since January.

There are some caveats: It could be the case that players “gave up” on reporting, but comparing report rates of other, non-AFK categories over time gives us confidence that this is a material change resulting from our work.

BETTER DETECTION, BETTER INFORMED

The good news from our work so far is that the various detections and interventions that we set in place to detect and penalize/deter AFKs seems to have made a meaningful impact on the frequency with which AFKs happen in your games.

But there’s more to be done!

For one, we can continue to improve detection. Since we first started work on AFKs, we broadened the different behaviors that qualify as an AFK in our system. As players get more… “creative” with how they AFK in game, so will our detection. The added bonus here is that a lot of the more clever AFK techniques tend to overlap with other unwanted behaviors in our game, such as intentionally feeding, griefing, or automated bot account farming (more on this in another article).

Second, we can keep you informed. Sharing both the process and results of our work to improve VALORANT’s community is an outlook to which we are committed. It’s something that you’ve told us you want. It’s one of the reasons we wanted to write these articles in the first place.

As we move ahead, we’ll continue to keep you posted on the state of the game, whether it be on the state of further reducing AFKs, or detecting and acting on some other behavior. What we ask in return is that you continue to provide questions, thoughts, feedback on what you want to see from us to make VALORANT a more safe, fun place to be.

You can find us on Twitter here and here (but we’re all over!).

Thanks for taking the time to read through this. Next time you hear from us, we’ll chat about toxic gameplay behaviors (friendly fire, sabotage, intentionally feeding, etc.).

Thanks!