7 months

ago -

PDX-Trinexx

-

Direct link

Welcome comrades! I’m Wokeg, and today we’ll be going over some of the upcoming changes to the scheme system, as well as some of the story content we’re adding for a few lucky landless adventurers this DLC.

My word count is going to be restricted in this Dev Diary because Community says that if I can’t edit myself down, they’ll edit it for me. Please send help.

[CM’s note: Woe, word-count limit be upon ye.]

► Discuss Dev Diary #157 on our forums![pdxint.at]

Schemes Alright, those of you who are paying attention will have likely seen the reworked schemes interface in several previous dev diaries — what have we done here, and why have we done it?

[The new intrigue window, with a murder scheme spinning up]

Put simply, we felt the old scheme system was a bit too random. It’s difficult to conduct political machinations when the machinery by which you politic is more of a catapult than a crossbow. It’d rarely be practical to have a foe murdered on a strict timer (say, for war or a timely inheritance), but more than that, it was very… binary.

You could either almost definitely pull a scheme off, or it wasn’t even worth attempting, with a very small middle ground for maybe-worthwhile schemes. This wasn’t helped by most positive aspects of a scheme being strongly positively correlated, so if your chance of doing it at all isn’t high, then you’ll likely also be slow and lacking in secrecy.

Likewise, when on the receiving end of a scheme, you were generally either completely safe or utterly screwed, with no real room for manoeuvre or concern due to changing circumstances and enemies. If I’ve got good intrigue and my spymaster likes me, you ain’t murdering me.

What we wanted to do was to significantly widen the gap in the middle between “scheme’s done the second I start it” and “scheme isn’t even worth attempting”, making it easier to both murder and be murdered by allowing characters to invest resources other than intrigue and gold in their schemes, as well as making agents more individually meaningful. The idea has been to give you more precise tools and interactivity within schemes, without notably increasing the micro required to conduct a basic one.

[An adventurer contract scheme]

Early on in development, we had actually intended for most of what adventurers do to be different varieties of schemes that would require vastly different characters as agents. This didn’t turn out quite how we’d hoped, so we iterated, and eventually pivoted away from it to the current contract model — a few scheme contracts are still scattered through adventurers, though, they’re just not the only thing they do.

Making Agents People We wanted to get away from agents as faceless masses of people who hate a scheme’s target and little else. Most of the time, you don’t even know who’s in your scheme unless they’re a victim’s spymaster.

Instead, we wanted agents to be — generally — just a few people who you pick carefully, fitting the right characters to the right job. What we’ve done to accomplish this is reduce the number of agents you get down to a general max of around 5, and give them each a specific role in the scheme, their agent type.

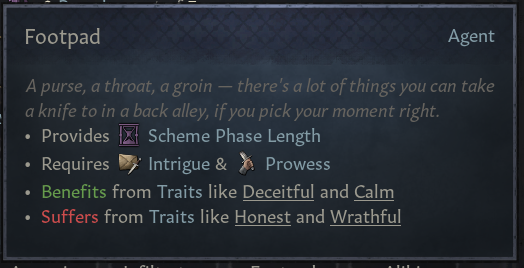

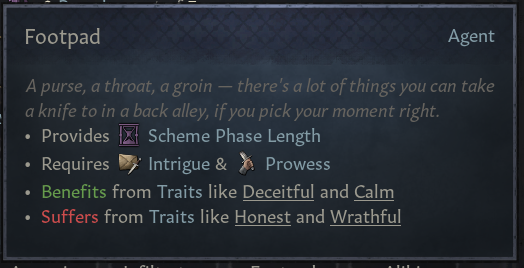

[The tooltip for an agent type, the Footpad, which makes schemes faster]

These roles all boost some aspect of the plot, so one might help it go faster, another helps keep it secret, and a third helps increase success chance. Different agent types have different requirements, so not every character is a good fit for every role, and different schemes have different agent types available.

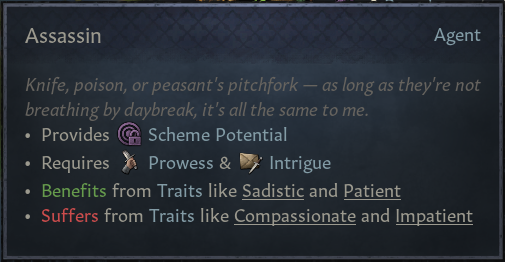

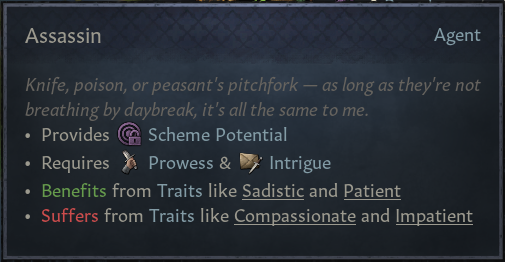

[The tooltip for an agent type, the Assassin, which increases a scheme’s maximum success chance]

At the start of a scheme, you choose which broad type of agents you want to focus on from a set of several packages, generally selecting between focusing on success chance, focusing on speed, focusing on secrecy, or going for a balanced mix. We initially trialled adding agents randomly over time from event options, letting the player select between two choices, but this proved frustrating and micro-intensive, so we moved away from it and towards the current system of pre-defined groups.

[The new murder interaction window]

What we hoped to create here was a situation where you might have different specialities within your scheme based on who you could get to join it, as well as be able to configure the same scheme type in different ways for different purposes — “here’s my speed-focused murder scheme, we’re gonna get the job done and fast but it won’t be quiet”, that type of thing.

In order to humanise them a bit more, we’ve also added a smattering of agent-specific (rather than scheme-specific) events. These let them have interpersonal conflicts, learn on the job, or bond over common hatreds, as well as dole out rewards for selecting agents that work well together and punishments for doing things like putting two nemeses in the same plot and asking them to work closely together.

[An agent event]

Lastly, we do still have an auto-invite agents button, so you don’t have to micro-manage agent adding if you don’t want to. The button won’t always grab the best person, and it won’t help you with bribes or anything, but if someone would be easy enough to murder, it’ll do the job.

Agent Acquisition Agents can now come from a broader pool, too; this changes a bit per scheme, but notably you can often bring in your own courtiers and vassals to help you conduct illicit business abroad, making intrigue-focused realms better able to wage war from the shadows without depending entirely on their targets’ weaknesses.

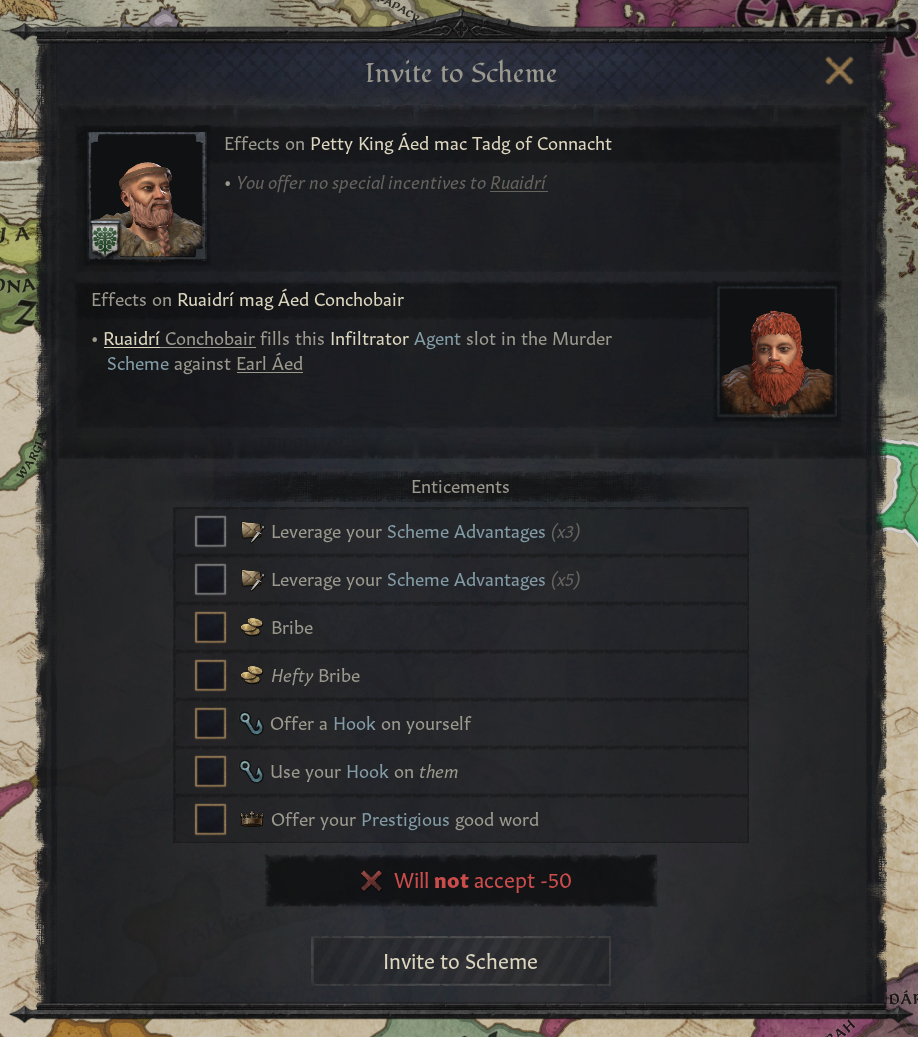

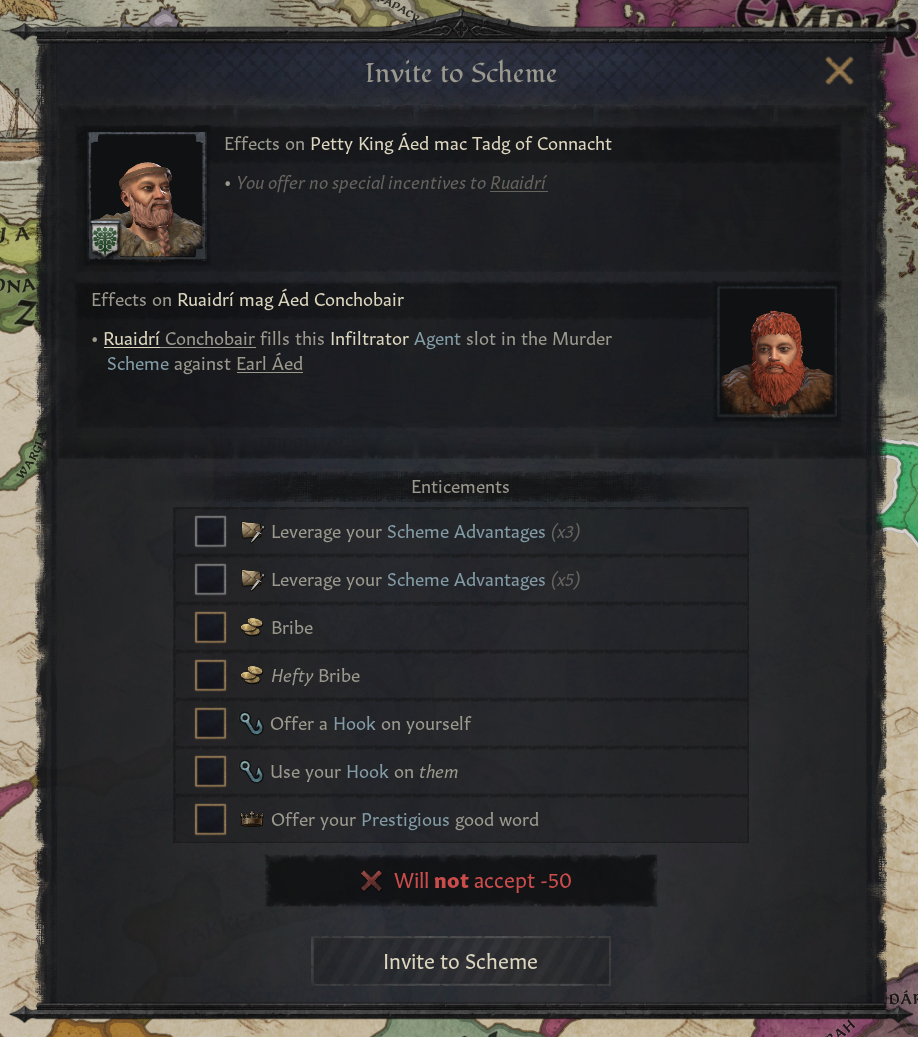

[Inviting an agent to a scheme, with many new bribes pictured — though not all]

In order to lure in better possible characters, we’ve added many new types of bribes besides hooks and gold: if you really, really, _really_ need someone dead, well, you can empty your treasury, expend your good word, maybe proffer land or use your scheme’s progress to sway them.

Anatomy of a Scheme Other than agents, the other big change we’ve made is to scheme progression.

Under the old system, a scheme had a random chance to progress every X months. This could be very slow and ponderous, and meant that (barring event content interference) you could not murder someone in less than ten months, regardless of your own skill or how much people hated them. Your chance to succeed was also largely fixed outside of adding more agents. You plod through the progress bar chunks, then you execute the scheme.

Under the new system, your success chance starts out low (sometimes below 0%, especially for higher tier targets), and grows over time up to a maximum. Instead of having a progress bar with discrete chunks, your speed determines the interval of time it takes to gain a boost of success chance. Every time you complete one of these phases, you gain an advantage point: you can use these to help you recruit agents and a certain amount are required to execute a scheme.

This means that you:

Start with a low chance to succeed (exactly how low mostly depending on the target).

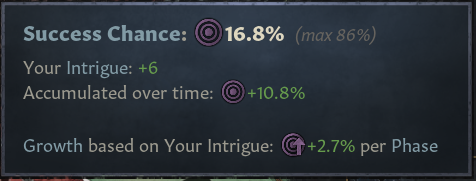

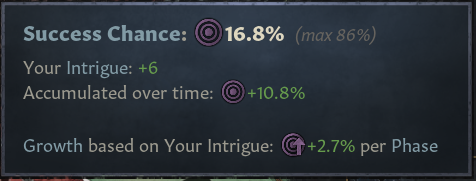

[The tooltip for a scheme’s current success chance, showing how much has been gained over time]

TL;DR = there’s a bar for success chance that grows over time, you affect how the bar grows over time and to what level, and you decide when you want to risk an ending.

Secrecy Since the new system makes schemes, on average, much shorter, we’ve also increased the frequency with which they’re detected. There’s a grace period of about six months, and then after that, a low chance to be detected monthly.

To help you make an informed choice about whether it’s worthwhile executing a scheme early, we’ve formalised the old system of segmented scheme discovery into a simple number that you can see in the interface, your scheme’s breaches. Every time your target gets a notification about your scheme, whether it be rumours of someone plotting to kill them or an agent rooted out or the actual scheme being exposed, that constitutes a breach.

When you hit the maximum number of breaches, your scheme is automatically destroyed.

Execution Once you’re ready, you execute (most) schemes manually. If you’ve accrued excess advantages, you can use them to boost your scheme success even further here. After you execute, the scheme proceeds just like it used to.

[Schemes may now be executed manually, as pictured]

This lets you make a meaningful choice on when to finalise your plans: is 60% success good enough if this dude is bearing down on me with an army? Can I simply murder a rival commander or troublesome spouse? How many breaches can we afford before discovery?

Likewise, we’ve done some magic behind the scenes to make the blocking of different types of murder a bit more consistent. The mechanics of this are a bit specific, but in short, rather than the prior system of determining which murder method was being used then looking to see if the victim had anything that might block it (which made balancing murder blocks virtually impossible), we roll two flat checks. One to see if they’ve got a one-use murder blocker (e.g., a dog throwing itself in front of the knife) — and then pick the highest from that list — and one vs. repeatable murder blockers (e.g., bodyguards), which takes a sum of all repeatable chances to a max of 75%.

Countermeasures, Odds, & Basic Schemes Another thing about schemes as-is is that… you can’t really do much about them. You can replace your spymaster (if you didn’t hire the best one you could before unpausing on day 1), and you can set them to Disrupt Schemes (if you weren’t already just defaulting to that).

To complement a more varied scheme system with more tools to interact with it from the schemer’s side, we’ve added scheme countermeasures. These provide ways to proactively oppose hostile schemes, acting a little bit like council tasks. Their benefits are varied and excellent for buying time, but each also comes with severe drawbacks that mean you don’t want to have one toggled on for long without good reason.

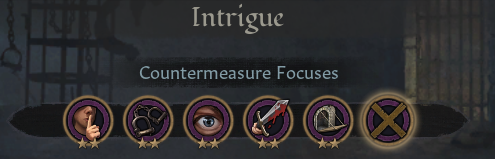

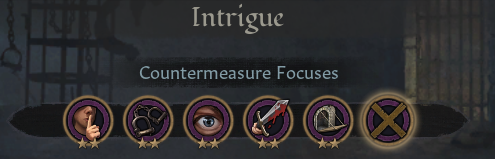

[The various countermeasure focuses]

If you suspect someone is plotting to murder you or seduce someone you don’t want seduced, countermeasures can give you a solid way to oppose them in the short to medium term at the cost of potential eventual instability.

All countermeasures come with different tiers, generally unlocked by religious tenets or cultural traditions, though sometimes traits help too. These generally lower the penalties and increase the effects, meaning that some cultures, faiths, and just people are better able to resist scheming than others.

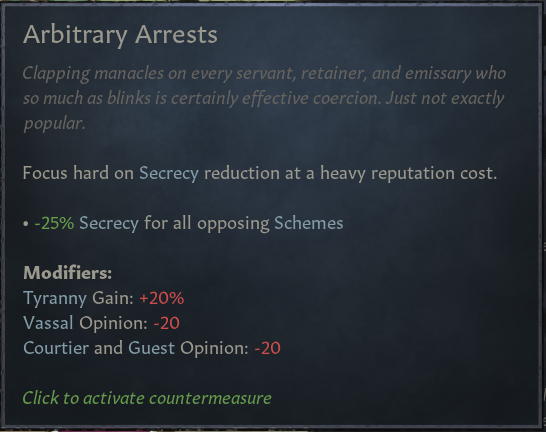

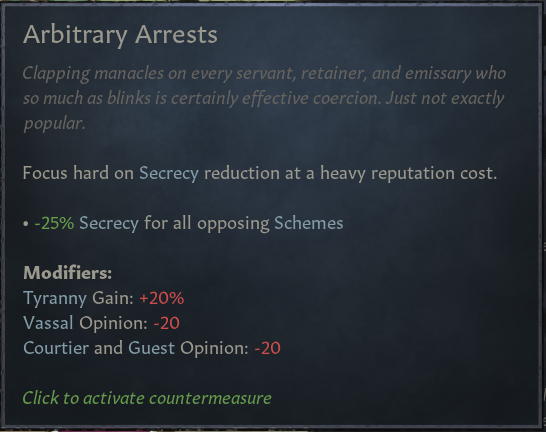

[A specific countermeasure, reducing opposing secrecy drastically for a significant cost]

Odds replace the old scheme chance prediction — they don’t give an exact value, because that’s very difficult to successfully build with the new mechanics, but they give a general idea of how likely a scheme is to succeed.

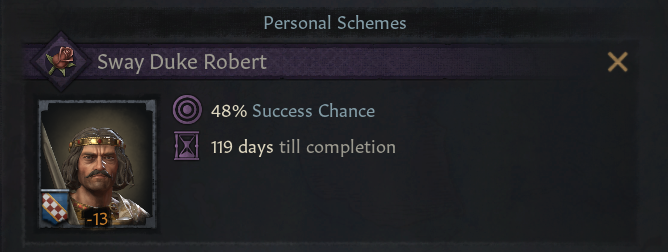

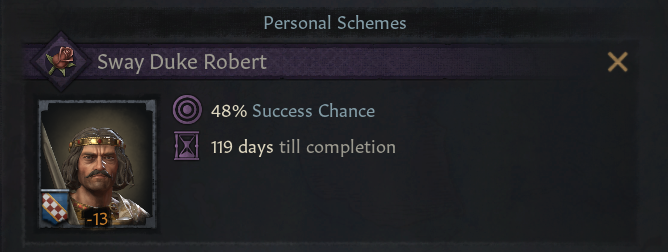

[Sway, a basic scheme, still uses simple mechanics]

Basic schemes are what we’ve done with schemes that don’t have agents: they have a simple success chance prediction ala the old system, and one long phase after which they execute automatically. We actually did experiment with adding agents to all schemes initially (even sway and seduction), but this proved very unfit for purpose during play-testing, so we created basic schemes as a way to allow plotting without all the extra clicks of the new agents system.

Stories Coming up this DLC, we’ve got some pre-scripted historical story content for four of our new landless adventurer characters. Unless I’m very much mistaken, this is CK’s first venture into this type of thing since Charlemagne aaaaallll the way back in CK2, and I’m sure some of you are curious as to why.

As people came over from the Legends of the Dead team to Roads to Power, we had a bit of a grey zone whilst they were onboarding to working on a different DLC.

We took a bit of a risk, and asked some of them to try making story content for our more famous landless adventurers — we had some really cool people lined up, and couldn’t easily represent why without giving them some bespoke mechanics (is it really Hassan Sabbah if you don’t found the assassins? Can you call Hereward Hereward if he never murders a Norman?). That just sorta ballooned into this experiment into narrative content.

As a result, we ended up with narrative content for four characters:

The size of this content is unevenly distributed, because the people making it had drastically different amounts of time given. We initially assumed everyone would get a very small amount of time to make just a little bit, which is what happened for El Cid, but then we found a bit more time for the person covering Hasan Sabbah, two designers collaborated (one from a different game team offering some spare time) on Wallada, and Hereward just… absolutely swelled in scope, because the designer allocated was able to spend much more time on him than expected.

We didn’t prioritise who got the most story content based on anything at all, it just worked out that El Cid got a light touch whereas Hereward got a whole sub-system.

[The new adventurer bookmark]

All story content is optional, so if you don’t want to engage in it, you don’t have to.

El Cid As El Cid, you’ll go through a small chain representing his travails through Iberia after being exiled by his foolishly-misled lord, King Sancho the Strong of Castille. As you progress, you will get opportunities to demonstrate your loyalty or assert your independence.

If you remain steadfast and resolute even in exile, King Sancho will doubtless eventually welcome you back to the fold (assuming he lives…), though a more ambitious Rodrigo may set his eyes on the prize of Valencia in the south.

El Cid also starts with many of his historical friends and family, like Alvar Fanez & Martin Antolinez, as well as his uncle, nephew, and mother. Alas, in 1066, he is not yet married, though his future wife Jimena de Oviedo is yet available to romance and elope with from her brother’s court.

He begins as a Sword-for-Hire, and has plenty of work for him amidst the Iberian Struggle.

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi Wallada is the last of the Umayyads in 1066, daughter of Caliph Muhammad of Andalusia, and inheritor of a great legacy and great wealth. Historically, she spent her life writing poetry, tutoring women at a school she founded, and generally causing consternation in her home city of Cordoba. She never married, nor did she have children, though she did take a broad variety of lovers, making her something of an eccentric by the standards of her time.

As an adventurer, her story content revolves around securing an adopted child, tactical use of seduction and romance, and writing and selling poetry in order to level up both her unique Violet Poet trait and the Double-Moon Tome (an artefact collating her works). She can also found a literary salon for the ages in a county of her choosing, once she has acquired suitably talented courtiers.

Wallada begins as a Scholar with ample starting gold and a decent prestige level. As she is quite old in 1066, her story may be inherited by her chosen successor and played for an additional generation.

Hasan Sabbah Hasan Sabbah is not a particularly religious teenager in 1066. He is, however, about to become one — after a chance encounter with an Ismaili preacher, he finds himself radicalised and set on a path to found the deadly Hashashins, eventually becoming the legendary Old Man of the Mountain.

As an adventurer, his story content lets him fast-track the religious conversion of counties. By doing so, he will eventually be summoned to Egypt, convert once more to Nizarism, and then take on the fierce might of Seljuk Persia. With the people of the land behind him (or not, depending on how conversion goes), Hasan tries to lead a revolution against the Sunni Turks.

Eventually, he may found the Assassins, leaving them in a mountain fastness to defend all good Nizaris going forwards.

Hasan starts play as a Scholar, though given the nature of the work set out before him, he may not stay one for long.

Hereward the Wake Hereward begins exiled to the continent, but unless there’s a player involved in the Conquest, he won’t stay that way for long.

The decisive win of William of Normandy puts a Norman yoke on English necks, and begins the elaborate mechanics of the Harrying of the North, where Hereward, William, Norman invaders, and Anglo-Saxon lords compete to pacify or incite the country’s populace to revolt against the new status quo. As he kills Normans and rallies the locals against their attacker, Hereward levels his unique trait, becoming a better and better guerrilla fighter in his native fenlands in the east of England.

Hereward begins play as a Freebooter, and history could hardly describe him as anything else.

Smaller Stories We’ve also got a smattering of smaller pieces of story content available — Prince Suleyman Qutalmishoglu, another bookmark character, has a small introductory event where he chooses how to react to his exile in the mountains of Cilicia…

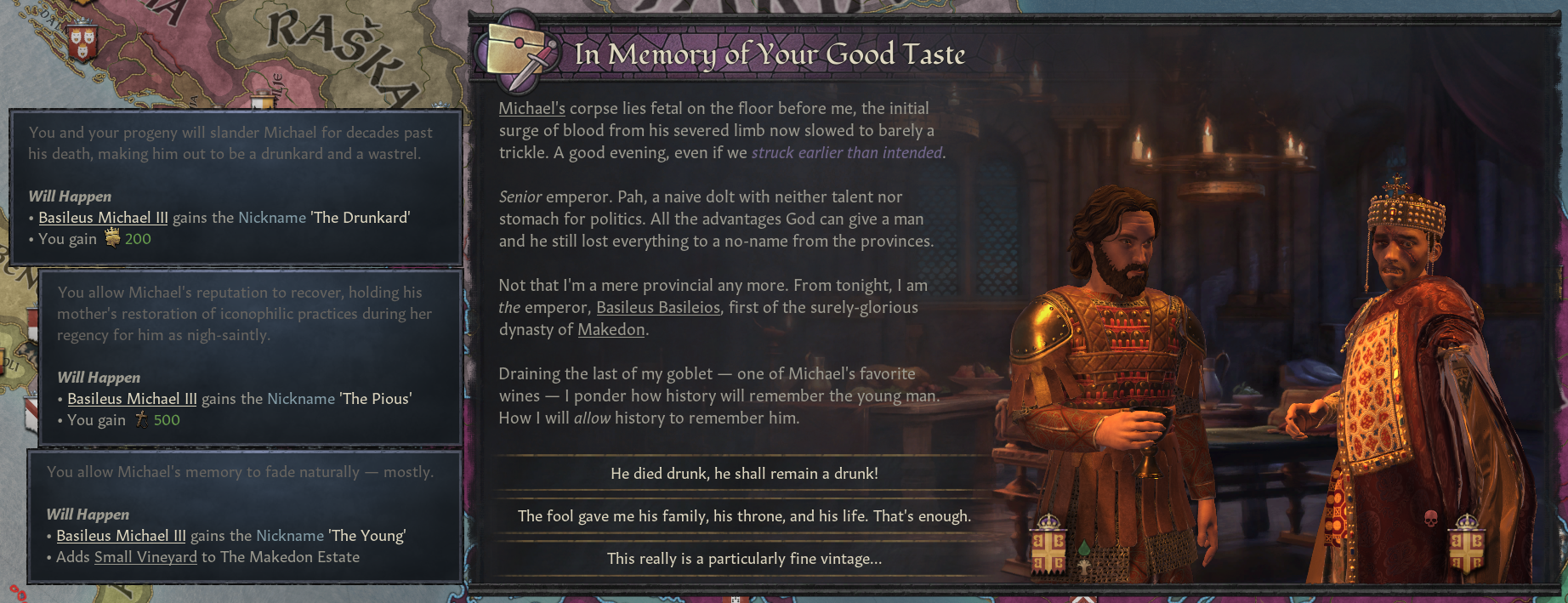

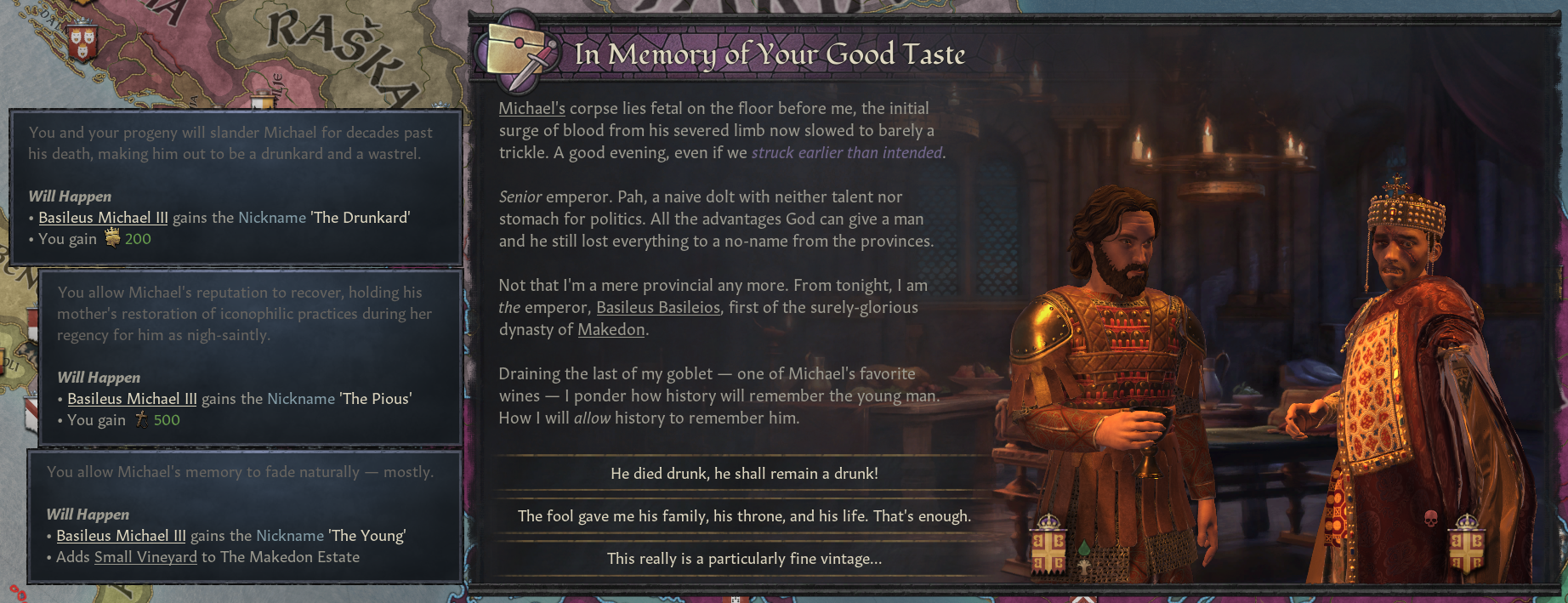

… Basileus Basileos has an introductory event featuring the (early) murder of his predecessor and a tie-in to the Many Roads to Power comic…

… and Siward Barn has a small chain forking off of Hereward’s content where you can go on to found the colony of New England in its natural, rightful, obvious place — the shores of the Black Sea.

Right, and that about does it for our final dev diary before release. Next week will be the release of Roads to Power itself!

Write glorious new sagas of military conquest and romantic adventures with Chapter III.

This Chapter includes two expansions, one event pack, and one cosmetic enhancement. Enjoy new mechanics, new events, and new historical flavor to add greater depth to Crusader Kings III!

https://store.steampowered.com/bundle/38036

Join the conversation and connect with other Paradox fans on our social media channels! Official Forums[forum.paradoxplaza.com] Official Discord[discord.gg] Steam Discussions[steamcommunity.com] Twitter[twitter.com] Facebook[www.facebook.com] Instagram[www.instagram.com] Youtube[www.youtube.com]

My word count is going to be restricted in this Dev Diary because Community says that if I can’t edit myself down, they’ll edit it for me. Please send help.

[CM’s note: Woe, word-count limit be upon ye.]

► Discuss Dev Diary #157 on our forums![pdxint.at]

Schemes Alright, those of you who are paying attention will have likely seen the reworked schemes interface in several previous dev diaries — what have we done here, and why have we done it?

[The new intrigue window, with a murder scheme spinning up]

Put simply, we felt the old scheme system was a bit too random. It’s difficult to conduct political machinations when the machinery by which you politic is more of a catapult than a crossbow. It’d rarely be practical to have a foe murdered on a strict timer (say, for war or a timely inheritance), but more than that, it was very… binary.

You could either almost definitely pull a scheme off, or it wasn’t even worth attempting, with a very small middle ground for maybe-worthwhile schemes. This wasn’t helped by most positive aspects of a scheme being strongly positively correlated, so if your chance of doing it at all isn’t high, then you’ll likely also be slow and lacking in secrecy.

Likewise, when on the receiving end of a scheme, you were generally either completely safe or utterly screwed, with no real room for manoeuvre or concern due to changing circumstances and enemies. If I’ve got good intrigue and my spymaster likes me, you ain’t murdering me.

What we wanted to do was to significantly widen the gap in the middle between “scheme’s done the second I start it” and “scheme isn’t even worth attempting”, making it easier to both murder and be murdered by allowing characters to invest resources other than intrigue and gold in their schemes, as well as making agents more individually meaningful. The idea has been to give you more precise tools and interactivity within schemes, without notably increasing the micro required to conduct a basic one.

[An adventurer contract scheme]

Early on in development, we had actually intended for most of what adventurers do to be different varieties of schemes that would require vastly different characters as agents. This didn’t turn out quite how we’d hoped, so we iterated, and eventually pivoted away from it to the current contract model — a few scheme contracts are still scattered through adventurers, though, they’re just not the only thing they do.

Making Agents People We wanted to get away from agents as faceless masses of people who hate a scheme’s target and little else. Most of the time, you don’t even know who’s in your scheme unless they’re a victim’s spymaster.

Instead, we wanted agents to be — generally — just a few people who you pick carefully, fitting the right characters to the right job. What we’ve done to accomplish this is reduce the number of agents you get down to a general max of around 5, and give them each a specific role in the scheme, their agent type.

[The tooltip for an agent type, the Footpad, which makes schemes faster]

These roles all boost some aspect of the plot, so one might help it go faster, another helps keep it secret, and a third helps increase success chance. Different agent types have different requirements, so not every character is a good fit for every role, and different schemes have different agent types available.

[The tooltip for an agent type, the Assassin, which increases a scheme’s maximum success chance]

At the start of a scheme, you choose which broad type of agents you want to focus on from a set of several packages, generally selecting between focusing on success chance, focusing on speed, focusing on secrecy, or going for a balanced mix. We initially trialled adding agents randomly over time from event options, letting the player select between two choices, but this proved frustrating and micro-intensive, so we moved away from it and towards the current system of pre-defined groups.

[The new murder interaction window]

What we hoped to create here was a situation where you might have different specialities within your scheme based on who you could get to join it, as well as be able to configure the same scheme type in different ways for different purposes — “here’s my speed-focused murder scheme, we’re gonna get the job done and fast but it won’t be quiet”, that type of thing.

In order to humanise them a bit more, we’ve also added a smattering of agent-specific (rather than scheme-specific) events. These let them have interpersonal conflicts, learn on the job, or bond over common hatreds, as well as dole out rewards for selecting agents that work well together and punishments for doing things like putting two nemeses in the same plot and asking them to work closely together.

[An agent event]

Lastly, we do still have an auto-invite agents button, so you don’t have to micro-manage agent adding if you don’t want to. The button won’t always grab the best person, and it won’t help you with bribes or anything, but if someone would be easy enough to murder, it’ll do the job.

Agent Acquisition Agents can now come from a broader pool, too; this changes a bit per scheme, but notably you can often bring in your own courtiers and vassals to help you conduct illicit business abroad, making intrigue-focused realms better able to wage war from the shadows without depending entirely on their targets’ weaknesses.

[Inviting an agent to a scheme, with many new bribes pictured — though not all]

In order to lure in better possible characters, we’ve added many new types of bribes besides hooks and gold: if you really, really, _really_ need someone dead, well, you can empty your treasury, expend your good word, maybe proffer land or use your scheme’s progress to sway them.

Anatomy of a Scheme Other than agents, the other big change we’ve made is to scheme progression.

Under the old system, a scheme had a random chance to progress every X months. This could be very slow and ponderous, and meant that (barring event content interference) you could not murder someone in less than ten months, regardless of your own skill or how much people hated them. Your chance to succeed was also largely fixed outside of adding more agents. You plod through the progress bar chunks, then you execute the scheme.

Under the new system, your success chance starts out low (sometimes below 0%, especially for higher tier targets), and grows over time up to a maximum. Instead of having a progress bar with discrete chunks, your speed determines the interval of time it takes to gain a boost of success chance. Every time you complete one of these phases, you gain an advantage point: you can use these to help you recruit agents and a certain amount are required to execute a scheme.

This means that you:

Start with a low chance to succeed (exactly how low mostly depending on the target).

- Grow your actual success chance by a certain amount every phase (exactly how much is mostly determined by your intrigue skill).

- Can increase your speed, giving you faster phases, by adding the right agents.

- Increase your maximum success, your scheme’s potential, by adding the right agents.

- The general idea is that high intrigue will very much aid you in speedy, stealthy kills, but strong agent composition is needed to get to the finish line reliably. Scheme potential is tied extremely heavily to agents, having a base of only 30%, so you can’t do schemes by yourself reliably.

[The tooltip for a scheme’s current success chance, showing how much has been gained over time]

TL;DR = there’s a bar for success chance that grows over time, you affect how the bar grows over time and to what level, and you decide when you want to risk an ending.

Secrecy Since the new system makes schemes, on average, much shorter, we’ve also increased the frequency with which they’re detected. There’s a grace period of about six months, and then after that, a low chance to be detected monthly.

To help you make an informed choice about whether it’s worthwhile executing a scheme early, we’ve formalised the old system of segmented scheme discovery into a simple number that you can see in the interface, your scheme’s breaches. Every time your target gets a notification about your scheme, whether it be rumours of someone plotting to kill them or an agent rooted out or the actual scheme being exposed, that constitutes a breach.

When you hit the maximum number of breaches, your scheme is automatically destroyed.

Execution Once you’re ready, you execute (most) schemes manually. If you’ve accrued excess advantages, you can use them to boost your scheme success even further here. After you execute, the scheme proceeds just like it used to.

[Schemes may now be executed manually, as pictured]

This lets you make a meaningful choice on when to finalise your plans: is 60% success good enough if this dude is bearing down on me with an army? Can I simply murder a rival commander or troublesome spouse? How many breaches can we afford before discovery?

Likewise, we’ve done some magic behind the scenes to make the blocking of different types of murder a bit more consistent. The mechanics of this are a bit specific, but in short, rather than the prior system of determining which murder method was being used then looking to see if the victim had anything that might block it (which made balancing murder blocks virtually impossible), we roll two flat checks. One to see if they’ve got a one-use murder blocker (e.g., a dog throwing itself in front of the knife) — and then pick the highest from that list — and one vs. repeatable murder blockers (e.g., bodyguards), which takes a sum of all repeatable chances to a max of 75%.

Countermeasures, Odds, & Basic Schemes Another thing about schemes as-is is that… you can’t really do much about them. You can replace your spymaster (if you didn’t hire the best one you could before unpausing on day 1), and you can set them to Disrupt Schemes (if you weren’t already just defaulting to that).

To complement a more varied scheme system with more tools to interact with it from the schemer’s side, we’ve added scheme countermeasures. These provide ways to proactively oppose hostile schemes, acting a little bit like council tasks. Their benefits are varied and excellent for buying time, but each also comes with severe drawbacks that mean you don’t want to have one toggled on for long without good reason.

[The various countermeasure focuses]

If you suspect someone is plotting to murder you or seduce someone you don’t want seduced, countermeasures can give you a solid way to oppose them in the short to medium term at the cost of potential eventual instability.

All countermeasures come with different tiers, generally unlocked by religious tenets or cultural traditions, though sometimes traits help too. These generally lower the penalties and increase the effects, meaning that some cultures, faiths, and just people are better able to resist scheming than others.

[A specific countermeasure, reducing opposing secrecy drastically for a significant cost]

Odds replace the old scheme chance prediction — they don’t give an exact value, because that’s very difficult to successfully build with the new mechanics, but they give a general idea of how likely a scheme is to succeed.

[Sway, a basic scheme, still uses simple mechanics]

Basic schemes are what we’ve done with schemes that don’t have agents: they have a simple success chance prediction ala the old system, and one long phase after which they execute automatically. We actually did experiment with adding agents to all schemes initially (even sway and seduction), but this proved very unfit for purpose during play-testing, so we created basic schemes as a way to allow plotting without all the extra clicks of the new agents system.

Stories Coming up this DLC, we’ve got some pre-scripted historical story content for four of our new landless adventurer characters. Unless I’m very much mistaken, this is CK’s first venture into this type of thing since Charlemagne aaaaallll the way back in CK2, and I’m sure some of you are curious as to why.

As people came over from the Legends of the Dead team to Roads to Power, we had a bit of a grey zone whilst they were onboarding to working on a different DLC.

We took a bit of a risk, and asked some of them to try making story content for our more famous landless adventurers — we had some really cool people lined up, and couldn’t easily represent why without giving them some bespoke mechanics (is it really Hassan Sabbah if you don’t found the assassins? Can you call Hereward Hereward if he never murders a Norman?). That just sorta ballooned into this experiment into narrative content.

As a result, we ended up with narrative content for four characters:

- El Cid

- Wallada bint al-Mustakfi

- Hasan Sabbah

- Hereward the Wake

The size of this content is unevenly distributed, because the people making it had drastically different amounts of time given. We initially assumed everyone would get a very small amount of time to make just a little bit, which is what happened for El Cid, but then we found a bit more time for the person covering Hasan Sabbah, two designers collaborated (one from a different game team offering some spare time) on Wallada, and Hereward just… absolutely swelled in scope, because the designer allocated was able to spend much more time on him than expected.

We didn’t prioritise who got the most story content based on anything at all, it just worked out that El Cid got a light touch whereas Hereward got a whole sub-system.

[The new adventurer bookmark]

All story content is optional, so if you don’t want to engage in it, you don’t have to.

El Cid As El Cid, you’ll go through a small chain representing his travails through Iberia after being exiled by his foolishly-misled lord, King Sancho the Strong of Castille. As you progress, you will get opportunities to demonstrate your loyalty or assert your independence.

If you remain steadfast and resolute even in exile, King Sancho will doubtless eventually welcome you back to the fold (assuming he lives…), though a more ambitious Rodrigo may set his eyes on the prize of Valencia in the south.

El Cid also starts with many of his historical friends and family, like Alvar Fanez & Martin Antolinez, as well as his uncle, nephew, and mother. Alas, in 1066, he is not yet married, though his future wife Jimena de Oviedo is yet available to romance and elope with from her brother’s court.

He begins as a Sword-for-Hire, and has plenty of work for him amidst the Iberian Struggle.

Wallada bint al-Mustakfi Wallada is the last of the Umayyads in 1066, daughter of Caliph Muhammad of Andalusia, and inheritor of a great legacy and great wealth. Historically, she spent her life writing poetry, tutoring women at a school she founded, and generally causing consternation in her home city of Cordoba. She never married, nor did she have children, though she did take a broad variety of lovers, making her something of an eccentric by the standards of her time.

As an adventurer, her story content revolves around securing an adopted child, tactical use of seduction and romance, and writing and selling poetry in order to level up both her unique Violet Poet trait and the Double-Moon Tome (an artefact collating her works). She can also found a literary salon for the ages in a county of her choosing, once she has acquired suitably talented courtiers.

Wallada begins as a Scholar with ample starting gold and a decent prestige level. As she is quite old in 1066, her story may be inherited by her chosen successor and played for an additional generation.

Hasan Sabbah Hasan Sabbah is not a particularly religious teenager in 1066. He is, however, about to become one — after a chance encounter with an Ismaili preacher, he finds himself radicalised and set on a path to found the deadly Hashashins, eventually becoming the legendary Old Man of the Mountain.

As an adventurer, his story content lets him fast-track the religious conversion of counties. By doing so, he will eventually be summoned to Egypt, convert once more to Nizarism, and then take on the fierce might of Seljuk Persia. With the people of the land behind him (or not, depending on how conversion goes), Hasan tries to lead a revolution against the Sunni Turks.

Eventually, he may found the Assassins, leaving them in a mountain fastness to defend all good Nizaris going forwards.

Hasan starts play as a Scholar, though given the nature of the work set out before him, he may not stay one for long.

Hereward the Wake Hereward begins exiled to the continent, but unless there’s a player involved in the Conquest, he won’t stay that way for long.

The decisive win of William of Normandy puts a Norman yoke on English necks, and begins the elaborate mechanics of the Harrying of the North, where Hereward, William, Norman invaders, and Anglo-Saxon lords compete to pacify or incite the country’s populace to revolt against the new status quo. As he kills Normans and rallies the locals against their attacker, Hereward levels his unique trait, becoming a better and better guerrilla fighter in his native fenlands in the east of England.

Hereward begins play as a Freebooter, and history could hardly describe him as anything else.

Smaller Stories We’ve also got a smattering of smaller pieces of story content available — Prince Suleyman Qutalmishoglu, another bookmark character, has a small introductory event where he chooses how to react to his exile in the mountains of Cilicia…

… Basileus Basileos has an introductory event featuring the (early) murder of his predecessor and a tie-in to the Many Roads to Power comic…

… and Siward Barn has a small chain forking off of Hereward’s content where you can go on to found the colony of New England in its natural, rightful, obvious place — the shores of the Black Sea.

Right, and that about does it for our final dev diary before release. Next week will be the release of Roads to Power itself!

Write glorious new sagas of military conquest and romantic adventures with Chapter III.

This Chapter includes two expansions, one event pack, and one cosmetic enhancement. Enjoy new mechanics, new events, and new historical flavor to add greater depth to Crusader Kings III!

https://store.steampowered.com/bundle/38036

Join the conversation and connect with other Paradox fans on our social media channels! Official Forums[forum.paradoxplaza.com] Official Discord[discord.gg] Steam Discussions[steamcommunity.com] Twitter[twitter.com] Facebook[www.facebook.com] Instagram[www.instagram.com] Youtube[www.youtube.com]